With everyone reading the 13fs filed last night, we see the quarterly drool-fest over what the super investors are doing. While it’s interesting to see what others are buying, I find it most interesting to learn why it is they are doing that buying. Sadly, one of my favorite super investors is a man named Kevin Douglas, and he, as usual, will not be filing any planned 13fs this quarter. Who is Kevin Douglas? Odds are you probably don’t know, yet over the past decade he has built one of the most impressive investment track records. Recently he has received some headlines for his thus far poor investment in American Superconconductor Corp., but even those articles reference the fact that he is little known above any other point (see the Wall Street Journal on the topic). If you do a Google Search for Kevin Douglas, it’s almost astonishing how little meaty information comes up for a guy who invests tens of millions at a time right now, in the age where Big Brother (aka the Internet) is always watching.

From what I can gather, Mr. Douglas made his initial money as the founder and Chairman of Douglas Telecommunications, a VoiP company. Beyond that, little is even know about Douglas Telecom (as it is/was known) for even the company’s website no longer exists. I found one old press release from the company that included a root directory phone number, but that line now leads to a perpetual busy signal. This only adds to the mystery and intrigue.

Swinging for the Fences, and Connecting

One may ask why I care, and that’s a fair question. I first encountered Mr. Douglas when he made a substantial investment in IMAX as the company seemed to be in a great deal of distress amidst the financial crisis, crumbling under its debt load accrued a decade earlier during the Dot.com. IMAX caught my eye at that time, as Dark Knight emerged as a hit on the platform and the catalyst to look deeper was Mr. Douglas, already the majority holder, ponying up for more shares in an equity raise that helped pay down a substantial chunk of the company’s debt load. Following that move, Mr. Douglas owned nearly 20% of the company and as a result, I dug further into Mr. Douglas’ portfolio holdings and investment track-record to determine whether that was a good or bad thing.

I was pretty amazed with what I found on two fronts: first, he had an outstanding success rate, as he made money on nearly all of his investments; and second, that nearly all of his successes were home runs. In baseball terms, this was not your all-or-nothing home run machine like a Jim Thome, nor was it your dinky little singles hitter like Ichiro. This was something like Barry Bonds in 2001 where each at bat was either a walk (a pass in investment terms) or a home run (greater than 25% CAGR over a substantial stretch of time).

For the most part, the only known investments by Mr. Douglas are in situations where he has taken in excess of the 5% ownership interest reporting threshold by the SEC, and as such, any picture is inevitably incomplete. That being said, by all appearances, when Mr. Douglas invests, he buys big and keeps on buying, plus he operates a fairly concentrated portfolio in companies with market capitalizations under $1 billion. He owns enough of companies to safely say that he doesn’t trade at all around the holdings, and sits tight as his money works for him. It’s this last element that is particularly impressive. He sits tight amidst volatility, he sits tight holding losses, and he sits tight holding massive gains. Patience is the man’s best friend.

Known investment successes include Hansen Natural, now Monster Beverages, Westport Innovations, Jos. A. Bank, Stamps.com, IMAX, and SilverBirch Energy, with one seemingly large failure in American Superconductor and a remains to be seen, although losing position in Cree Inc. right now.

Monster Beverages and Westport happen to be two of the market’s top performers over the last two years, and they just so happen to be two of Mr. Douglas’ most noteworthy investments. In Monster Beverages, formerly Hansen Natural Corporation, Mr. Douglas bought 329,719 shares at an average price of $0.58 between 2003 and 2004. At today’s share price of $109.68 that represents a 92% CAGR, having turned around $190 thousand into a sum greater than $36 million (Hat Tip to Stockpup for the cost basis info).

With Westport Innovations, Mr. Douglas accumulated 18.5% of the company’s shares, at prices between $12.95 and $20/share. Let’s assume an average price of roughly $18/share (which is high if anything considering he had plenty of purchases, most of which happened below that price), that represents a 144% return over the last year and a half. Whereas Monster/Hansen generated a stellar return on a relatively small sum, Mr. Douglas put over $150 million to work in WPRT and thus far has seen an equally lucrative outcome in terms of percent return, and a far more impressive outcome in terms of gross return. Don’t underestimate for a second how hard it is to double $150 million in contrast to any number in the thousands.

How Does he Do It?

Considering how little is known about Mr. Douglas, it’s hard to know exactly how or what he looks for in an investment. However, I have spent a decent amount of time digging into each and all of his known investments during since 2003 and drawn several conclusions. First, it’s most clear what Mr. Douglas doesn’t look for. He doesn’t look much at all at economic forecasts, or anything of that kind, and further, Mr. Douglas is neither a traditional “value” nor “growth” investor. In many respects, he operates far more like a venture capitalist operating in public markets, than a traditional equity strategist. Incidentally, the only clear-cut theme one can glean from his present holdings is that Mr. Douglas has a “thing” for Canada, as many of his investments are companies domiciled in Canada. Yet, that appears more of a coincidence than anything else, and is most likely reflective of the fact that many American investors turn to “sexier” countries like the BRICs when looking abroad, while ignoring our neighbor to the north.

My intuition after reviewing as many investments as I can is that Mr. Douglas first assesses a company’s addressable market and then assigns probabilities based on the likelihood of the company capturing different portions of the addressable market. For example, let’s say we’re talking about a company with a $20 billion addressable market. He would then assign probabilities for the company to capture that market opportunity. For example, let’s say there is a 20% chance that the company captures 50% of the market, a 50% chance of the company capturing 30% of the market, and a 30% chance that the company captures 10% of the market, he then calculates the weighted average of the future revenue base (.2*$10) + (.5*$6) + (.3*$2) = $5.6 billion. So long as the company is worth less than the present market capitalization grown at his target rate of return (let’s say 25%), he will invest. For a $5.6 billion market opportunity five years down the road, that means Mr. Douglas will be buying so long as the company is worth less than $1.8 billion today, Mr. Douglas will be buying.

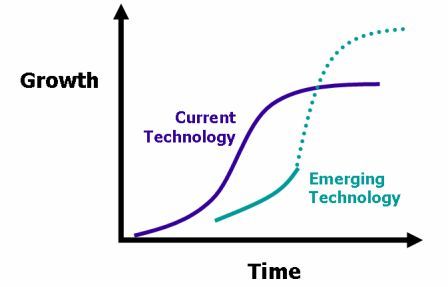

Each of these investments are positioned for some kind of secular super-trend, some of which people knowingly acknowledge and talk about, others of which Mr. Douglas is clearly early in recognizing the opportunity. All in all, there are two key elements to his analysis: first is the subjective analysis of the companies’ business and market opportunity, and next is the objective mathematics, based on probabilistic outcomes and his CAGR objectives. It is in these subjective metrics that his skill is clearly superior. His ability to identify and quantify market opportunities for his portfolio companies is simply uncanny. Whether it is energy drinks, fine men’s apparel, digital postage or a movie display platform, Mr. Douglas has tremendous skill at identifying the largest market opportunities, targeting the company best positioned to prosper, and quantifying the investment upside in order to make a concentrated wager. Call me impressed.

Mr. Douglas, if you’re out there and reading this, I would love to get in touch with you in order to learn a little bit more about your investment background and process.

Update: I have added a follow-up post to give some more color and background on the AMSC loss and the HANS/MNST gain. Plus I added a brief little bit about Mr. Douglas very successful investment in Rural Cellular Corp. Be sure to check it out.

Author Disclosure: Long IMAX, CREE

Elliot Turner Posted on

Elliot Turner Posted on  Thursday, March 8, 2012 at 3:23PM

Thursday, March 8, 2012 at 3:23PM

New RGA Investment Advisors Market Commentary