Buffett, Soros and Uncle Sam

Elliot Turner Posted on

Elliot Turner Posted on  Tuesday, October 8, 2013 at 1:35PM

Tuesday, October 8, 2013 at 1:35PM I recently came across an interesting piece comparing the returns of Warren Buffett and George Soros (h/t @ReformedBroker). The post immediately caught my attention, for both Buffett and Soros are two of my favorite minds in investing. I am oversimplifying greatly, but from Buffett, I learned much about the importance of patience, quality and management integrity, while from Soros, I learned the importance of identifying self-fulfilling cycles and reflexive processes in financial markets. While some like to contrast these two gentlemen as taking opposing views to markets, I think their approaches are not mutually exclusive. In fact, combining the lessons from these two gentlemen has been a potent force in crafting my own, unique approach to investing.

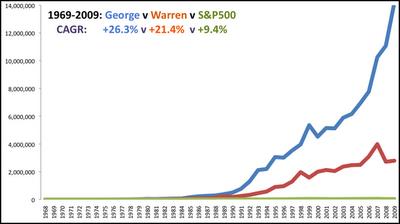

In the piece comparing the relative performance of Buffett and Soros, the author includes the following chart:

The author then asks, if “George's track record is better but Warren is richer. Why?” while offering the following answer:

The snowball of POSITIVE compounding for longer. Both were born in August 1930 and Warren ran his hedge fund from 1957 but George didn't set up his until 1969. Warren was lucky to be in Omaha while Dzjchdzhe Shorash was in Budapest, more affected by WW2. Also Warren got into currency trading and philanthropy later. George's outperformance is due to stronger international diversification and because reflexivity is ignored. Value investing is copied more than reflexivity investing. The boom bust of Eurozone sovereign credits and subprime CDOs are quintessential examples of reflexivity. Crises are PREDICTABLE. And profitable if you have expertise.

Sure some of these factors certainly played a role in Buffett’s wealth relative to Soros, though this is largely misleading and the most crucial point is ignored entirely. Simply put, these return figures are not presented on an apples to apples basis. Buffett’s returns are presented using the growth in Berkshire Hathaway’s book value, while Soros’ returns are presented using his hedge funds’ returns. In this comparison, the author is therefore comparing Buffett’s after-tax returns, with Soros’ pre-tax returns. (There is a second key point missed that many Buffett followers will pick up on: book value does not reflect the true realizable value of many Berkshire assets, and therefore, is understated relative to the intrinsic value of the company. While important, my intent here is to focus simply on the tax consequences so beyond this mention, I will skip digging into the consequences of this reality).

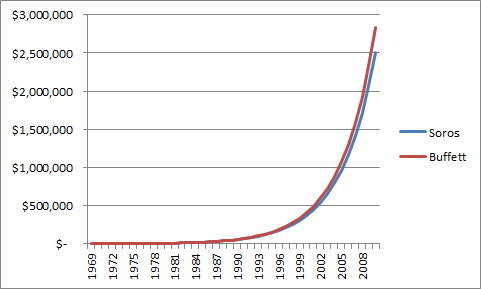

We can re-plot the relative returns of Soros and Buffett in order to more closely portray what the comparative returns would look like on an after-tax basis. For the purposes of this comparison, I assumed that each year, 20% of Soros’ returns would be paid out in taxes. This is obviously a simplification, and not intended to be historically accurate, as everyone has their own unique tax profile, and long and short-term trades have different consequences. I am merely cherry-picking a number that if anything, is probably favorable to Soros in light of the following factors: 1) capital gains tax rates were higher than today’s 15% during much of the time period covered in this analysis; 2) we know that Soros profited in capital markets subject to hybrid tax rates between long and short-term capital gains (like commodity and foreign exchange markets); and, 3) from Soros’ own journal in Alchemy of Finance (which I strongly recommend reading), we know that he engaged in many short-term, speculative trades that would be subject to ordinary income tax rates.

There is a second simplification I’ve made for the purposes of this comparison in assuming that returns were earned on a straight-line basis, rather than calculating each individual’s returns per year, adjusting for taxes and plotting those out. Again, the purpose here is to demonstrate the impact of taxes on returns, and not to be perfectly precise with who is better than whom.

Another very simple effect I very seldom see discussed either by investment managers or anybody else is the effect of taxes. If you're going to buy something which compounds for 30 years at 15% per annum and you pay one 35% tax at the very end, the way that works out is that after taxes, you keep 13.3% per annum. In contrast, if you bought the same investment, but had to pay taxes every year of 35% out of the 15% that you earned, then your return would be 15% minus 35% of 15% or only 9.75% per year compounded. So the difference there is over 3.5%.And what 3.5% does to the numbers over long holding periods like 30 years is truly eye-opening. If you sit back for long, long stretches in great companies, you can get a huge edge from nothing but the way that income taxes work.

I am a fan and student of Mr. Buffett and Mr. Soros and have no bone to pick in this race, though it should be clear to all that both men’s returns are about as good as they get over such a long time-frame. To summarize, there are two key points here that I want to emphasize. For individual investors, it’s extremely important to plan your investments in such a way as to maximize after-tax, not pre-tax returns. Don’t be fooled simply by the appreciation in your portfolio. Think about what portion of your gains you are paying to Uncle Sam (taxes) come April 15th each year. For those who work with investment managers or invest via funds, when looking at performance reports, it’s extremely important to think about what the after-tax returns of a strategy look like.

Disclosure: Long shares of BRK.B in my own and client accounts.

Reader Comments